The terrorist attacks in Paris have rocked our global sensibilities. In the media business, a two- or three-day story is a big deal. In this case, almost a week later, people from around the world are still trying to sort out what the attacks mean. Everyone has an angle – free speech, terrorist tactics, religious tolerance, immigration, weapons control, intrafaith beliefs, law enforcement, etc. I’m interested in all those things – some more than others – but my main gig is interfaith education for kids. I also have two kids of my own. Talking with them about the attacks shed new light on how my training in developmental psychology informs my parenting. So here are my suggestions based on both my education and my personal experience.

The single most important thing to do when talking about controversial or sensitive issues with your kids is to ask them questions. I simply cannot emphasize this enough. I’m a pretty involved parent with a Ph.D. in cognitive development. Despite that, or maybe because of it, I’m regularly amazed by my incorrect assumptions about what my kids know. We’ll start with my son who is 8 years old and in the third grade. He attends a public elementary school and regularly attends Sunday School at Jubilee! church, the progressive Christian church where I work. He had not yet asked about the Paris attacks, and when I asked if he had heard of them, he said, “No.” Of course, now that I had brought it up, he wanted to know more. Here’s a portion of our ensuing conversation. (S=son, M=me/mom)

M: Do you know what the word “religion” means? What does it mean to be part of a religion?

S (shrugging shoulders): I don’t know.

M: Do you know what it means to be “Christian”?

S: Not really.

M: Do you know what people do in church?

S: Yeah. Duh. They talk about Jesus and love and stuff.

M: Do you know what it means to be Buddhist or Muslim?

S: No.

M: Do you know what it means to be Jewish?

S: Well, yeah. They celebrate Hanukkah!

I was surprised to learn that he really didn’t understand the concept of religion very well. Clearly, a conversation about “fundamentalist Islam” was going to be well beyond his reach. I shouldn’t have been so surprised; his responses mesh almost perfectly with what developmental psychologists have learned about the minds of children based on over a century of research. Put simply, up until the age of about 6, children aren’t very good with abstract concepts – like “religion” or “belief.” Even then, kids begin to show rapid gains in these cognitive skills only after puberty. My son has some understanding of common abstract notions – like “beauty” or “fairness.” But he really struggles with more advanced abstract concepts – like “justice” or “values” – and he struggles with the idea that definitions can vary widely from person to person or group to group.

Elementary school kids are also just learning about sub-categories and multiple memberships. Like other kids his age, my son is capable of understanding that our dog is both a dog and a Jack Russell mix. He can also understand that he is my son, my mothers’ grandson, and my sister’s nephew. However, it would be rather difficult for him to understand that there are different belief systems within the faith traditions. Frankly, there are plenty of adults who don’t understand this either.

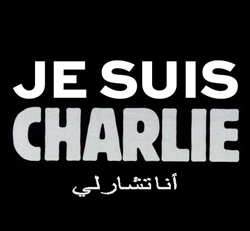

The conversation with my daughter was significantly more advanced. She is a first-year student at a public high school and regularly attends the Sunday School/youth group at Jubilee! church, where we use the Bible-based interfaith curriculum I developed. Last night, she asked my husband and me about the attacks. Actually, what she asked was, “What does ‘Je Suis Charlie’ mean?” She has taken French, so she can translate the phrase word-for-word, but the overall meaning was lost on her. Apparently, various images were showing up on Snap Chat, a messaging app. that allows users to send photos, videos, and drawings to a group of recipients. She scrolled through the “snaps” which included numerous images of “Je Suis Charlie” signs, rally banners, and Paris street memorials. Here are some of her responses to the questions I asked her. My husband, a lawyer and history buff, was also part of the conversation (D=daughter; H=husband)

M: So what do you know about “Je Suis Charlie”?

D: Nothing. I’m just seeing all these images, so it seems like something is up.

M: Have you heard of ISIS, ISIL, or al-Qaeda?

D: Yes. All three.

M: What about Boko Haram?

D: No.

M: Boko Haram is responsible for all those schoolgirls being abducted in Nigeria.

D: Oh, yeah. I’ve heard of that.

M: Do you know what it means if I say, “fundamentalist Islam”?

D: No.

M: Do you know what it means if I say, “fundamentalist Christian”?

D (very tentatively): Uh…that they are right wing conservatives?

M: Do you know that, in modern-day Islam, it is generally regarded as wrong to show images of the Prophet Muhammad?

D: Yes.

M: Do you know what the 1st amendment to the Constitution is about?

D: Oh, I should know that. We learned a lot about the Constitution and the preamble and the amendments last year in school. Uh…freedom of speech?

H: Yep. And what else?

D: Freedom of the press?

H: Yep. And what else?

D: Freedom of religion.

Clearly, my daughter is operating on a much higher cognitive level. Some of her abilities are typical of kids her age. Most notably, she has a much broader knowledge base, and she is much more capable of thinking about abstract concepts. She has visited Paris, so she knows where it is. She has learned about different faith traditions – partly at Jubilee! church and partly in her history classes. She also knows that belief differences exist both within and across those traditions. However, her knowledge base is still somewhat rudimentary, and some of my assumptions were wrong. For starters, she didn’t know as much as I thought about current events. She clearly hadn’t heard about the Paris attacks until then, and she could not remembering hearing about Boko Haram. She also thinks of “fundamentalist Christianity” in terms of politics rather than religious belief, which is probably why that knowledge didn’t help her infer what “fundamentalist Islam” might look like. Her knowledge is clearly idiosyncratic, but her responses helped me better understand the details. She actually knew more than I realized about the first amendment, which was heartening.

I was now ready to explain the Paris attacks. It is important to share facts that are grounded in what your kids already know. That’s why starting with questions is so important. I didn’t know in advance how I was going to explain the Paris attacks, but my questions helped lay the foundation for the upcoming conversation. To my son I said something like this:

In Paris, which is a big city in the country of France, there were some people who worked at a magazine. They drew funny cartoons. Well, some people thought the cartoons were funny and interesting; other people thought the cartoons were really mean. Sometimes, the cartoons would make fun of people’s religions – what they believe about God. Some people were so mad, they shot and killed the people who drew the cartoons. On top of that, someone else went to a Jewish restaurant. His plan was to kill Jewish people because they are a different religion. And now lots of people are really, really upset.

To my daughter I said something like this:

There’s a magazine in Paris called Charlie Hebdo. It’s a satirical magazine. I’m not sure we have the exact same thing in the U.S, but it’s sort of like Mad Magazine or the Onion. They make fun of things as a way to get people to think about them. They often made fun of religious beliefs – all religious beliefs. But their cartoons depicting Muhammad were understandably offensive to Muslims. Frankly, they were offensive to me. I believe in free speech, so I think they should be able to publish those kinds of cartoons. But I don’t really find the cartoons funny, and I probably would not buy Charlie Hebdo if I lived in France. Anyway, some Muslims associated with al-Qaeda broke into the magazine offices and shot a bunch of people. Several were killed; others were wounded. Then, another terrorist took hostages and killed people at a Jewish deli. People from all over the world are using the phrase “Je Suis Charlie” to show their support for free speech and to make a statement against terrorism in general.

My son’s response was this:

“Ok – you mean some people drew cartoons and other people killed them?! Wow. That’s crazy. Those crazy people should get into a lot of trouble!”

“Well,” I said, “The people who did the shooting all died, so they did get into a lot of trouble.”

His response totally matched what we know about moral development. Younger children tend to see things in black and white, and they don’t really care why people act the way they do. The classic research tool for this work is modeled after the “Heinz dilemma” which goes something like this:

A woman was dying from a special kind of cancer. There was one drug that doctors thought might save her, but it was very expensive. A pharmacist in town had the drug, but the woman’s husband couldn’t afford to buy it. He went to everyone he knew to borrow the money, but he still didn’t have enough, so the husband decided to steal the drug for his wife. Should he have stolen the drug? Why or why not?

Researchers read these types of paragraphs to kids of various ages and record their responses. What matters is not whether the kids answer “yes” or “no” to the criminal behavior; what matters is the reasoning behind their answers.

Younger kids tend to focus more on the crime itself and the possibility of punishment: the husband should not have stolen the drug because stealing is bad and now he will go to jail. The reasoning of older kids/teenagers tends to include underlying motivations, ethical principles, and human rights. As expected, my daughter’s response to my description of the Paris attacks was much more nuanced. She can understand why terrorists might be prompted to behave in violent ways, she can understand the global denunciation of the attacks (on various grounds), and she can understand how the two attacks were related but different. I told her that she could go on line and search for images of Charlie Hebdo cartoons and of related cartoons drawn since the attacks.

Despite our wistful desire for easy answers in these types of situations, no one can tell you exactly what to say when talking to your kids about controversial/sensitive issues. The conversations with my children certainly should not be used as scripts that you follow word-for-word. Each child is different and each situation is different. However, developmental research into cognitive and moral development has provided insights into how kids think over the course of childhood. Those findings offer useful guidelines for interpreting what kids are actually asking about. That’s why it’s so important to start with questions. Before you get tangled up in long, complicated explanations, find out what your child knows, and use that information to determine what they want/need to know. You might be surprised by what you hear. I know I was.